Introduction: Your Roadmap to Successful Cotton Procurement

When a buyer or designer specifies 100% cotton fabric, they are requesting a product that has completed a complex journey, transforming a raw agricultural commodity into a sophisticated, engineered textile.

Our Factory Experience & Expertise

As a textile manufacturing team with over 20 years of experience, we have guided numerous garment factories and home textile brands through this process. Our daily work isn’t just selling cloth; it’s managing this transformation—from sourcing raw yarn to conducting lab tests for shrinkage and colorfastness, and solving bulk quality issues before a single roll ships.

Many people understand the basics, but the key to successful sourcing—lies in understanding how decisions made at each stage create the final product. Why is one T-shirt silky smooth while another is rough and hairy? Why does one pair of jeans shrink while another holds its shape?how cotton is made into fabric?The answers are engineered, not accidental.

Why This Guide Matters

This guide is based on our hands-on experience with thousands of orders, not just textbook theory. We will walk you through the entire cotton manufacturing process, from a boll of raw cotton to a finished bolt of fabric, breaking down each technical step.

When we say you must specify yarn twist, it’s because we have seen the costly failures that happen when you don’t. This is the operational playbook we share with our partners, designed to empower you with the expert knowledge to source confidently.

What Is Cotton?

Before we enter the factory, let’s define our raw material. Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of cotton plants. Botanically, it is the most widely used natural fiber in the textile industry process, composed almost entirely of cellulose. Its molecular structure makes it hydrophilic (water-loving), which gives it its signature properties of softness, breathability, and absorbency.

Industry Data:

To understand its importance, consider the global scale. According to industry reports like the Textile Exchange Preferred Fiber & Materials Report, total global fiber production in 2023 was approximately 124 million metric tons. Of this, cotton fiber accounted for about 24.4 million tons.

This macro-structure directly impacts raw material pricing, availability, and lead times. Furthermore, a growing portion (approx. 28%) of this cotton is part of sustainable programs (like BCI (British Compatibility Index), Organic, etc.), which are becoming a critical compliance and traceability requirement for many international brands.

Cotton has numerous uses in our lives: cotton fibers are used to make clothing in the textile industry; cottonseed kernels are used to make edible oil in the food industry; cottonseed hulls are used to make natural culture media for fungi in the agricultural industry; and cotton can be used in the medical field to make cotton swabs, gauze, etc.

What Is Cotton Fabric?

Simply put, cotton fabric (or textile cloth made of cotton) is the finished material created by taking raw cotton fibers and processing them into yarn, and then weaving or knitting that yarn into a coherent structure.

The term define cotton fabric is broad because the final product can be as thin as medical gauze, as crisp as shirting poplin, as stretchy as a knit t-shirt, or as durable as heavy denim. The properties of the final fabric are determined by the process we are about to explore.

So, How Is Cotton Made into Fabric?

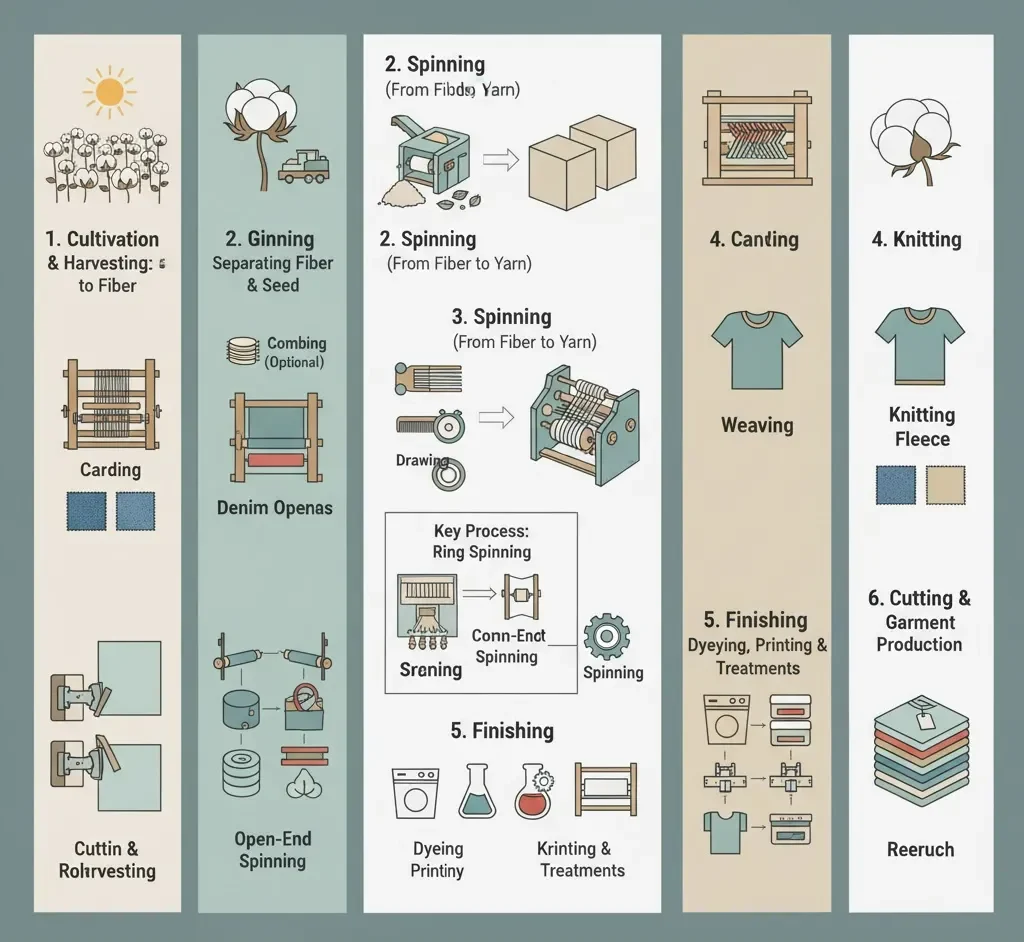

The journey from a raw cotton material to a finished bolt of cloth is a multi-phase fabric production process. We can break this down into four critical engineering stages:

- Raw Material Pre-Processing: Cleaning and purifying the fiber.

- Spinning: Creating yarn from the fiber.

- Fabric Formation: Weaving or knitting yarn into cloth.

- Finishing: Dyeing, printing, and applying final treatments.

Phase 1: Raw Material Pre-Processing (From Seed-Cotton to Clean Fiber)

This is the fixed, foundational stage. You cannot make good fabric from poorly prepared fiber. The goal here is to get from a harvested lump of seed-cotton to a pure, clean, and aligned sliver of fibers.

1) Ginning

- Purpose: The cotton ginning process is the first mechanical step after harvesting. Its sole purpose is to separate the cotton fibers (lint) from the cotton seeds. The result is bale lint, which still contains 3%–5% impurities (leaves, stems, dirt).

- Equipment: The choice of machine is critical. Saw Gins are high-capacity (10-50 tons/day) and used for the vast majority of Upland (medium-staple) cotton. For premium long-staple cottons, Roller Gins are preferred. They are slower but gentler, reducing fiber damage.

- Details: After ginning, the lint is pressed into dense bales. In our QC, we specify that the fiber integrity rate must be ≥95% and check for any residual seeds, which can cause severe damage to downstream machinery.

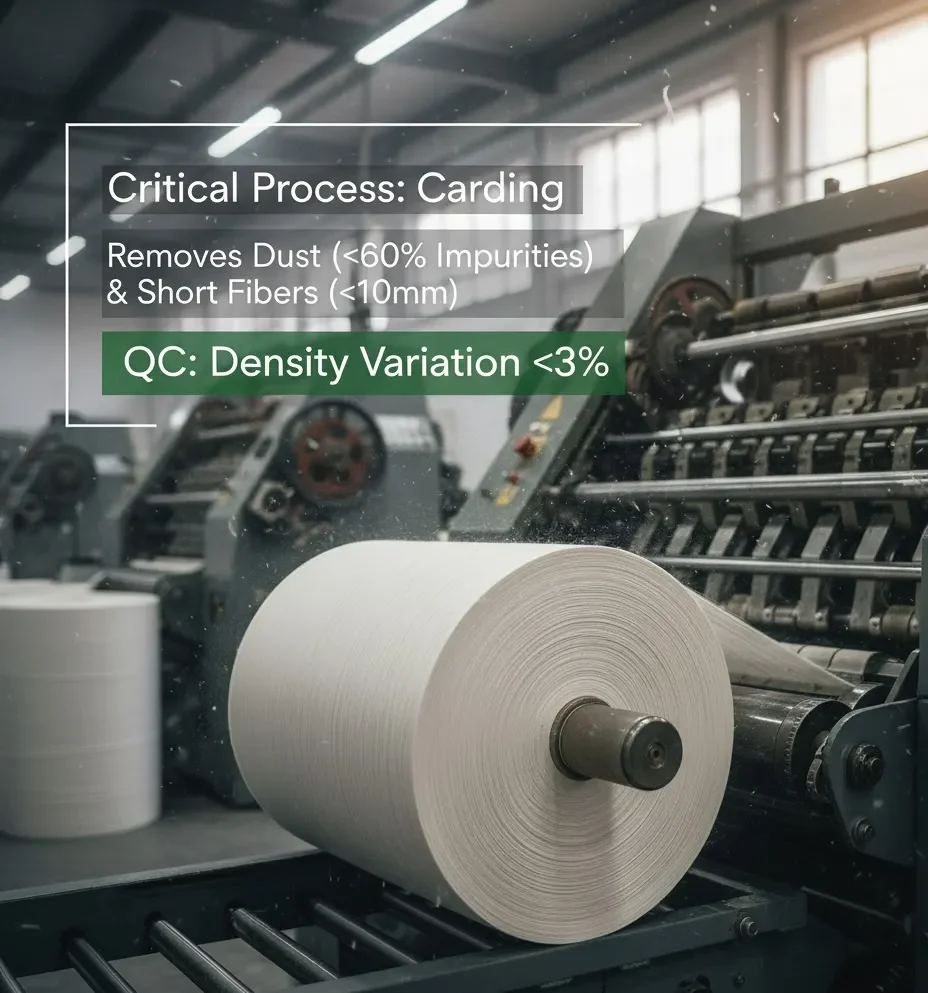

2) Cleaning

- Purpose: The bale of lint is opened, blended, and cleaned. The process involves Opening (breaking up the compressed cotton blocks), Cleaning (removing the remaining impurities), and Blending (mixing cotton from different bales to ensure uniform quality). The final output is a consistent lap or cotton roll.

- Equipment: This is a line of machines: Bale Openers, Pre-Cleaners (using beaters and dust cages), Blenders, and Scutchers.

- Details: This process is critical for removing dust (which can be 60% of all impurities) and short fibers (<10 mm). A typical finished roll is 20-30 kg, 1.5 m wide, and must have a density variation of less than 3% to ensure the resulting yarn is even.

Phase 2: Spinning (From Fiber to Yarn)

This is where the first major branching decisions occur. The methods chosen here will define the yarn’s final cost, hand-feel, and strength.

Step 1: Choosing a Purification Method (The Carded vs. Combed Choice)

This is a “choose your own adventure” for quality. Every yarn must be carded, but only premium yarns are combed.

Option A: Carded Cotton (Standard, Cost-Effective)

- Carding : The cleaned cotton lap is fed into a Carding machine… This produces a carded sliver, a rope of fibers with about 80% parallelization.

- Drawing : To optimize uniformity, 6-8 carded slivers are blended and stretched (drafted) together on a Draw Frame. This is done twice. The final drawn sliver is highly uniform (unevenness <2%) and has ~30% greater fiber cohesion.

Option B: Combed Cotton (Premium, High-Purity)

- Carding : Same as the carded process. The resulting sliver still has a short fiber rate of 15%-20%.

- Combing : This is the crucial extra step. The slivers are fed into a Comber, which uses needles and rollers (300-500 cycles/min) to perform an extremely fine filtering, removing 60%-80% of the remaining short fibers and all micro-impurities. The final combed sliver has a short fiber rate of ≤5% and fiber parallelization of ≥95%.

- Drawing : Same as the carded process, but the resulting sliver is even more uniform (unevenness <1.5%).

Factory Experience

When a client is developing high-end solid-color shirting, premium pima cotton t shirts, or baby apparel, we will always recommend using combed cotton yarn, specifically combed ringspun cotton. We will then write key performance indicators directly into the Purchase Order (PO), such as Pilling Resistance (ISO 12945-2) ≥ Grade 3.5 (after 2000 cycles) and Dimensional Stability (Shrinkage) (ISO 5077 / AATCC 135) ≤ 3%.

Why? Because the combing process removes the short fibers that cause pilling, and the uniformity of the yarn makes the final fabric far more stable during dyeing and finishing. This reduces downstream quality complaints and customer returns. The test methods AATCC 135 and ISO 5077 are the universally accepted standards for measuring shrinkage.

Step 2: Spinning Process (Carded / Combed Slivers)

After drawing, the sliver goes to roving (for ringspun/compact) and then spinning.

1) Roving : (This step is skipped by Open-End spinning).

Purpose: The drawn sliver is too thick to be spun directly. Roving drafts it (stretches it 5-10 times), adds a slight twist (50-100 twists/meter) for strength, and winds it onto a bobbin. The resulting “roving” is a finer, stronger strand (0.5-1 g/m).

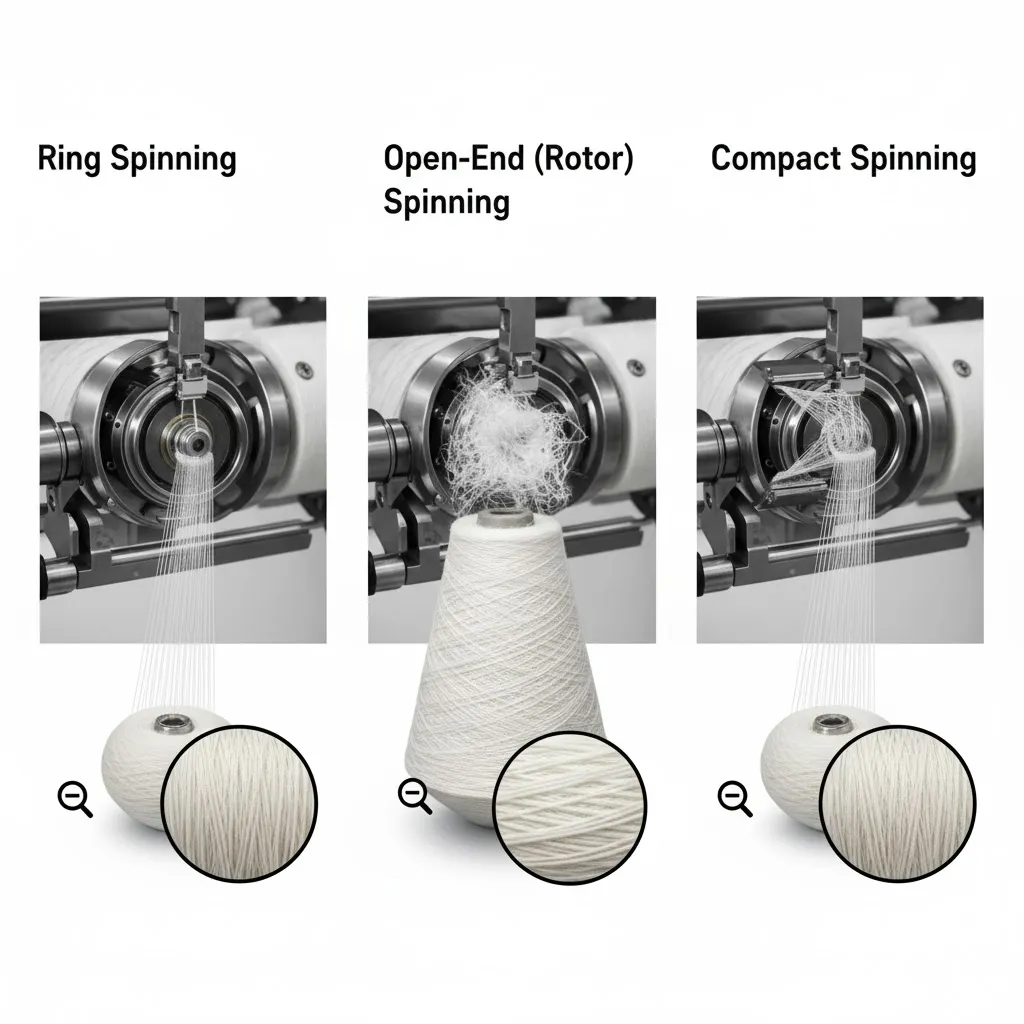

2) Choosing a Spinning Method (The 3 Choices)

This is the second major decision point, defining the yarn’s final feel and cost.

- Option A: Ring Spinning (Traditional, High-Quality)

Purpose: To draft the roving and apply a high degree of twist, creating a fine, strong, and smooth yarn.

Equipment: Ring Spinning Frame. The roving is drafted 10-50 times and twisted by a small traveler moving on a ring at 8,000-12,000 r/min.

Details: This slow, mechanical twisting process locks fiber ends securely into the yarn. It’s ideal for finer yarns (≥32s count) and results in the softest, strongest yarn (strength ≥25 cN/tex). This is the classic ring spun cotton (or ringspun) yarn.

- Option B: Open-End (Rotor) Spinning (Efficient, Economical)

Purpose: To create a medium-to-coarse yarn directly from the drawn sliver (skipping roving) at very high speeds.

Equipment: Open-End (Rotor) Spinning Machine. The sliver is opened into individual fibers, fed into a high-speed rotor (spinning cup) at 30,000-50,000 r/min, and twisted into yarn by the air current and rotation.

Details: The resulting open end yarn is hairier, weaker (strength ≥20 cN/tex), and bulkier. However, its production speed is 3-5 times faster than ring spinning, making it highly cost-effective. It’s ideal for yarns ≤21s count, used in heavy fabrics like denim, workwear, and towels.

Industry Case Study

The choice of open-end is often driven by cost and efficiency. For example, spinning machinery leaders like Saurer promote their Autocoro rotor spinning machines with technologies like ‘SynchroPiecing’ that can increase productivity by up to 30% (depending on machine/conditions). For our clients producing high-volume, cost-sensitive items like utility towels or promotional hoodies, this efficiency gain allows us to deliver a strong, heavy fabric at a highly competitive price.

- Option C: Compact Spinning (Premium, Ringspun Upgrade)

Purpose: An upgrade to ring spinning that uses air to condense the fibers, dramatically reducing hairiness and increasing strength.

Equipment: A ring spinning frame with an added compacting zone (e.g., a perforated drum with air suction, 0.2–0.5 MPa).

Details: This process nearly eliminates all surface fuzz (hairiness removal ≥80%) and increases strength by 10%-15% over standard ring spinning. It’s the ultimate yarn for luxury shirting and super-fine bedding (≥100s count).

3) Winding :

Purpose: The final step. The small bobbins from spinning are wound onto large, cone-shaped packages (“cones”) for shipping.

Equipment: Autowinder. This machine also inspects the yarn, cuts out any defects (slubs, neps, weak spots), and re-splices the ends, ensuring a consistent, knot-free 1-3 kg cone.

Phase 3: Fabric Formation (From Yarn to Greige Fabric)

This is where the 1D yarn becomes 2D cloth. The choice here dictates stretch, structure, and stability.

Option A: Woven Cotton (Stable Structure)

- Process: Interlacing two sets of yarns at right angles.

- Warping : Hundreds of yarns are wound from cones onto a large warp beam, perfectly parallel and under uniform tension (error <5%).

- Sizing : The warp beam is unwound and the yarns are coated in a protective size (starch/PVA) to increase their strength (↑30%-50%) and prevent breaking…

- Drawing-in : Each individual warp yarn is threaded through a harness and a reed (a comb that dictates fabric density, e.g., 20-40 dents/cm).

- Weaving : The warp yarns are loaded onto the loom (Air-Jet, Water-Jet, or Rapier). The harnesses lift specific warp threads (the shed) while a weft yarn is shot across at high speed (300-500 m/min), creating the fabric. The weave (Plain 1:1, Twill 2:1, Satin 5:3) is determined by the lifting pattern.

Option B: Knitted Cotton (Natural Stretch)

- Process: Interlocking loops of yarn.

- Preparation: Cones of yarn are simply placed on a creel (yarn rack) to feed directly into the machine. No warping or sizing is needed.

- Knitting : The yarns are fed to needles on a circular (for T-shirt fabric) or flat (for collars) knitting machine, which form them into interlocking loops.

- Weft Knitting : The most common method. Yarns run horizontally. Creates stretchy fabrics like Jersey and Rib Knit . Horizontal stretch ≥50%, perfect for t-shirts.

- Warp Knitting : Yarns run vertically in a zig-zag pattern. Creates more stable knits like tricot or mesh, often used for sportswear. Breathability ≥500 mm/s.

Phase 4: Finishing (From Greige Fabric to Finished Cloth)

This is the magic stage that gives the raw, greyish greige fabric its final color, feel, and function. It’s a complex, multi-step chemical and mechanical process.

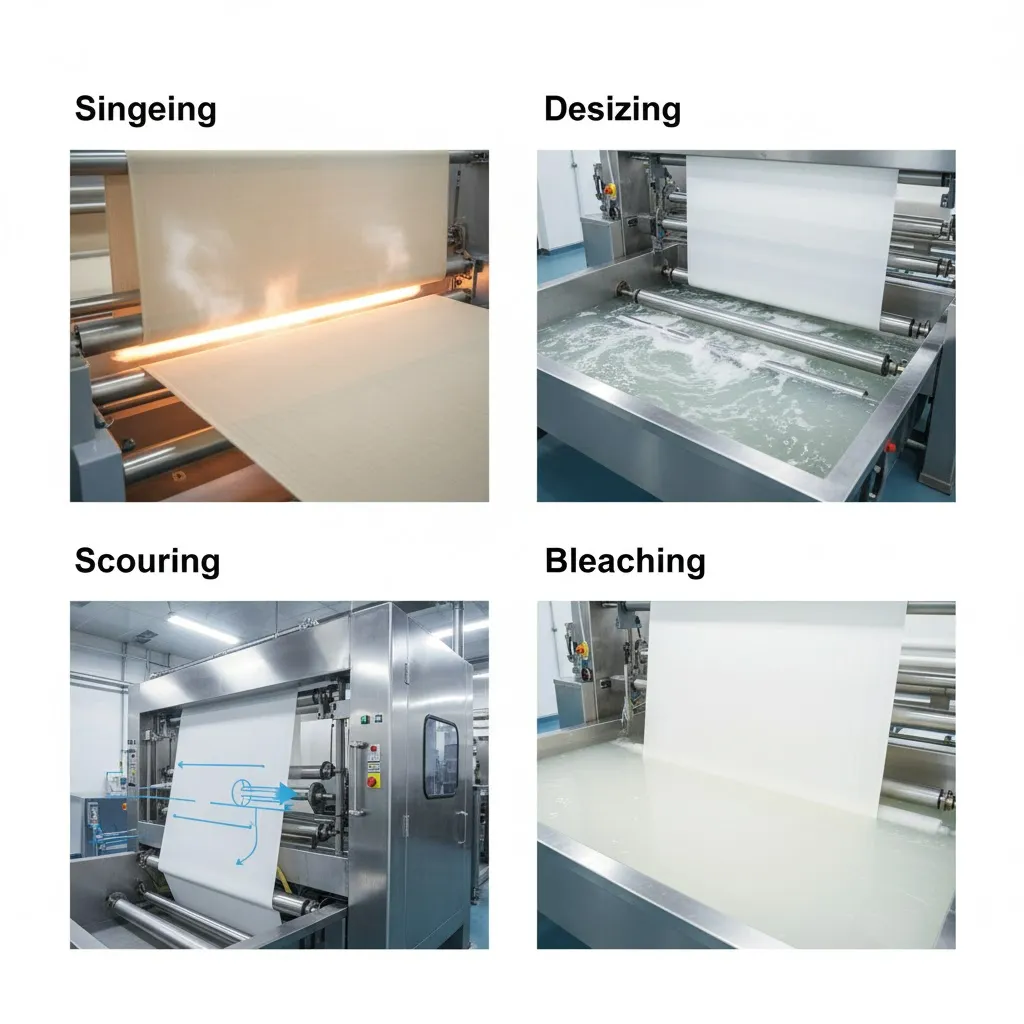

(A) Pre-Treatment (The Essential Cleanup)

- Singeing : The fabric is passed at high speed (80-120 m/min) over a gas flame (800–1000 °C) to burn off all surface fuzz (fuzz removal ≥90%).

- Desizing : A hot enzyme bath (50–60 °C, pH 6–7) dissolves and removes the starchy sizing applied during weaving, making the fabric absorbent again.

- Scouring : A hot alkaline bath (95–100 °C, NaOH 30–50 g/L) removes natural waxes, pectins, and dirt from the cotton fibers.

- Bleaching : A hydrogen peroxide bath (90–95 °C, pH 10–11) removes all natural color, resulting in a uniform white base (whiteness ≥85%).

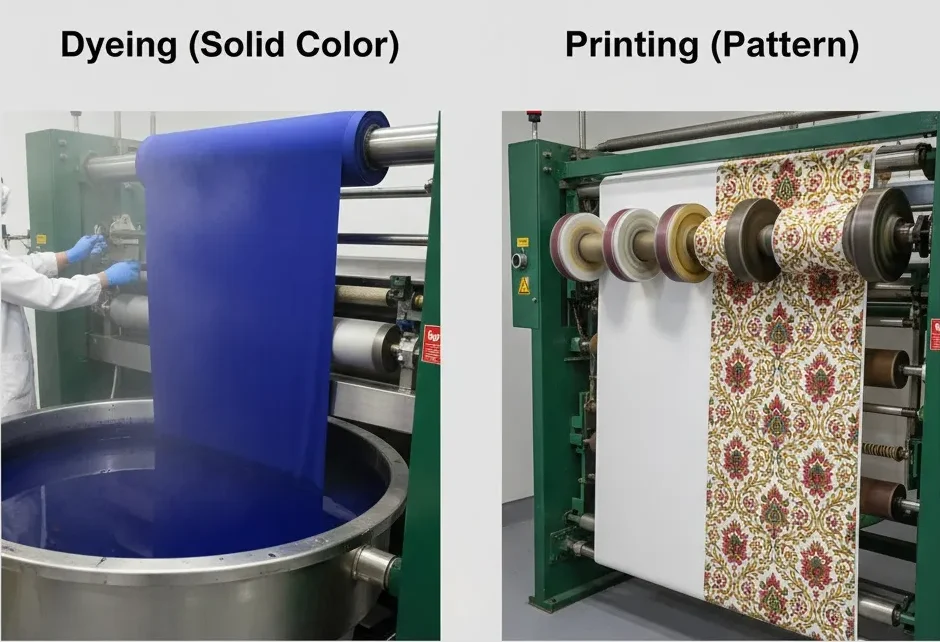

(B) Dyeing / Printing (Adding Color & Pattern)

- Option A: Dyeing (Solid Color): The fabric is saturated in a dye bath. For cotton, we use Reactive Dyes, which form a strong chemical bond for excellent wash fastness (Grade ≥3-4 perISO 105-C06) and minimal color deviation (ΔE <1.5).

- Option B: Printing (Pattern): Color is applied to localized areas using screens or digital printers. The fabric is then steamed (100–105 °C) to fix the color, followed by washing to remove excess dye.

(C) Finishing (Applying Final Properties)

1) Basic Finishing (Required):

- Stentering : The damp fabric is stretched on a frame and passed through a hot oven (120–150 °C). This dries the fabric, sets its final width (width tolerance <±1%), and corrects any skewing (skew ≤1%).

- Sanforizing : A final mechanical pre-shrinking process using steam and rubber blankets to achieve a stable shrinkage rate of 1%-3%.

- Softening: A final rinse with softeners (10–20 g/L) to give the fabric its target hand-feel.

2) Appearance Finishing (Optional):

- Calendering : High-pressure hot rollers iron the fabric to give it a high-gloss, flat finish (gloss ≥80 GU).

- Emerizing/Brushing : Abrasive rollers create a soft, peachy, or fuzzy surface (flannel), (fuzz 0.3–1 mm).

3) Functional Finishing (Optional):

- Wrinkle-Resist: A resin (DMDHEU 80–120 g/L) is applied and cured (150–170 °C) to give the fabric “easy-care” properties.

- Water Repellent : A fluorocarbon-free finish (20–50 g/L) is applied to make water bead off the surface (hydrostatic pressure ≥10 kPa).

- Antibacterial : A finish (e.g., silver ion) is applied to inhibit bacterial growth (kill rate ≥99%, wash durable).

- Mercerizing : A high-end treatment for luxury cotton using a strong NaOH solution (28%-30%) under tension. This strengthens the fiber by 20%-30% and dramatically increases its luster and ability to take dye.

Factory Practice Data

To show the real-world impact of these processes, we ran parallel tests on three common greige fabrics after their full finishing cycle:

| Fabric Spec | Shrinkage (ISO 5077 / AATCC 135) | Pilling (ISO 12945-2, 2000 revs) | Breathability (ASTM D737) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Woven Poplin, 120 gsm (Combed) | -2.0% (Warp) / -1.8% (Weft) | Grade 3.5–4.0 | N/A |

| Woven Twill, 260 gsm (Carded) | -2.5% (Warp) / -2.0% (Weft) | Grade 3.0–3.5 | N/A |

| Knit Jersey, 180 gsm (Combed) | -1.8% (Length) / -2.0% (Width) | Grade 3.5-4.0 | 120 cfm |

These test methods are the common international standards that we write into our Purchase Orders (POs). Citing them (e.g., [External Link: ASTM D737] for breathability) ensures both the buyer and the mill are aligned on quality expectations and significantly reduces disputes.

What Are the Uses of Cotton Fabric?

After this complex fabric making journey, the final product is ready for its mission. The applications are endless and directly tied to the processes used:

Apparel Fabrics

Characteristics: Prioritizes comfort, softness, drape, breathability, and style.

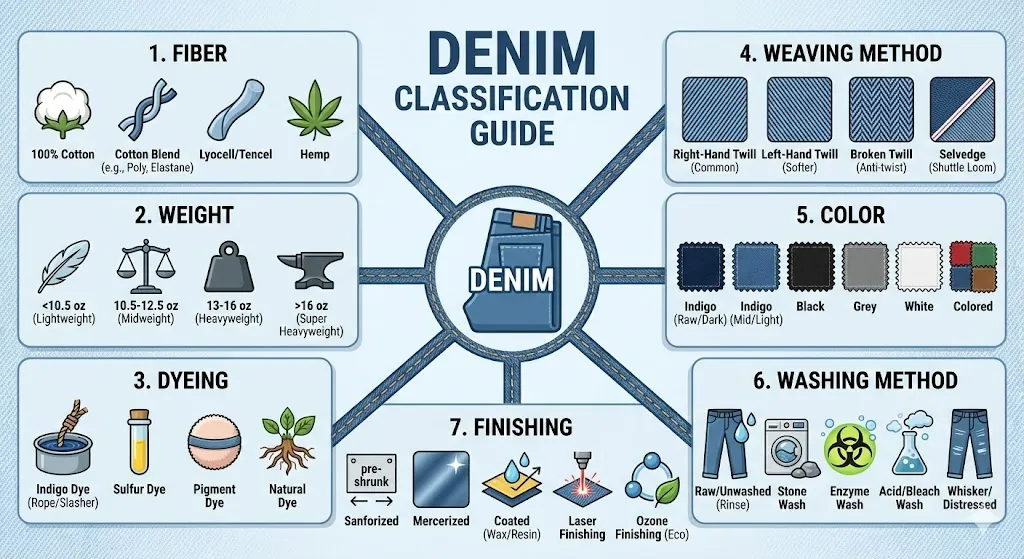

Fabrics Covered: Jersey (Knit), Poplin (Woven, Plain), Denim (Woven, Twill), French Terry (Knit), Pima Cotton Fabrics (Material), Sateen (Woven, Satin).

(Browse our curated selections at [Internal Link])

Home Textiles

Characteristics: Prioritizes durability, washability, aesthetic, and specific functions (e.g., absorbency, light-blocking).

Fabrics Covered: Sateen (Bedding), Printed Cotton (Curtains), Terrycloth (Woven, Pile for towels), Canvas (Upholstery), Flannel (Pajamas, sheets), Corduroy (Pillows).

Industrial & Technical Textiles

Characteristics: Prioritizes a specific function over all else—strength, absorbency, filtration, or stiffness.

Fabrics Covered: Gauze (Woven, Plain – for medical filtration), Canvas (Woven, Plain – for industrial tarps, bags), Buckram (Process – for stiffness in apparel/books).

What Are the Cotton Sourcing Pathways?

As a B2B buyer, once you understand this process, you have three main ways to source:

Sourcing from a Trader/Wholesaler:

Pros: Low MOQ, fast delivery (stock service), wide variety.

Cons: Higher price, no control over the production process or specs.

Sourcing from a Factory/Mill (Direct):

Pros: Best price, full customization of every step you just read, full QC traceability.

Cons: High MOQ (1000m+ per color is common), longer lead times.

Sourcing via an Agent:

Pros: A hybrid model; you get expert guidance to manage factory relationships and QC.

Cons: Requires paying a commission.

(No matter which path you choose, a professional procurement process is vital. For a complete overview, see our Strategic Cotton Sourcing Guide.)

Conclusion

From a humble boll of raw cotton to a finished, high-performance textile, the cotton fabric making process is an engineering journey of precise, critical decisions. Every step—from the 0.1mm gap on a carding machine to the 150°C curing temperature for a finish—is a lever we can pull to design a fabric that meets your exact needs for cost, performance, and feel.

Cotton fabric quality is not an abstract concept; it is meticulously manufactured.

As a manufacturer with full control over this entire process, we don’t just sell fabric; we offer technical solutions. If you’re looking for a partner who understands and can execute on these details, we invite you to contact us and let our engineers help you build your next product.

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

What is the main difference between Ringspun and Open-End spinning?

Ringspun is a traditional, premium process that twists fibers into a smooth, strong yarn (like twisting a rope), resulting in a soft, durable fabric. Open-End is a high-speed, economical process that uses air to tangle fibers into a yarn, resulting in a hairier, stiffer, but more cost-effective fabric.

Why is Combed Cotton more expensive?

Combed cotton is more expensive because it goes through an extra mechanical step (combing) that removes 15-20% of the fiber volume as waste (short fibers). You are paying a premium for a purer, stronger, and smoother yarn, which requires more raw material and more machine time.

What is the difference between Woven and Knitted cotton?

Woven fabric (like denim or shirting) is made on a loom by interlacing straight warp and weft yarns, making it stable and structured. Knitted fabric (like a t-shirt) is made with needles to create interlocking loops, giving it natural stretch and softness.

(For more, see our deep dives: Fabric Weave Types Explained and Knitted Cotton Fabric).

How do I ensure my fabric doesn’t shrink?

You must specify Sanforized (pre-shrunk) fabric in your purchase order. This mechanical process ensures the fabric’s residual shrinkage is within an acceptable range (e.g., under 3%). Always verify this by requesting a lab test report based on a standard like AATCC 135 or ISO 5077.

What is the difference between Carded and Combed cotton?

Carded cotton is the standard; its fibers are detangled and aligned. Combed cotton takes carded cotton and puts it through an additional combing step to remove all the short, scratchy fibers, resulting in a significantly smoother and more premium fabric.